The Bhagavad Gita ] often referred to as the Gita is a Hindu scripture, dated to the second or first century BCE,[7] which forms part of the epic Mahabharata. It is a synthesis of various strands of Indian religious thought, including the Vedic concept of dharma (duty, rightful action); samkhya-based yoga and jnana (knowledge); and bhakti (devotion).[8][b] It holds a unique pan-Hindu influence as the most prominent sacred text and is a central text in Vedanta and the Vaishnava Hindu tradition.

While traditionally attributed to the sage Veda Vyasa, the Gita is probably a composite work composed by multiple authors.[9][10][11] Incorporating teachings from the Upanishads and the samkhya yoga philosophy, the Gita is set in a narrative framework of dialogue between the pandava prince Arjuna and his charioteer guide Krishna, an avatar of Vishnu, at the onset of the Kurukshetra War.[6]

Though the Gita praises the benefits of yoga[12][13] in releasing man's inner essence from the bounds of desire and the wheel of rebirth,[6] the text propagates the Brahmanic idea of living according to one's duty or dharma, in contrast to the ascetic ideal of seeking liberation by avoiding all karma.[12] Facing the perils of war, Arjuna hesitates to perform his duty (dharma) as a warrior. Krishna persuades him to commence in battle, arguing that while following one's dharma, one should not consider oneself to be the agent of action, but attribute all of one's actions to God (bhakti).[14][15]

The Gita posits the existence of an individual self (jivatman) and the higher Godself (Krishna, Atman/Brahman) in every being;[c] the Krishna-Arjuna dialogue has been interpreted as a metaphor for an everlasting dialogue between the two.[d] Numerous classical and modern thinkers have written commentaries on the Gita with differing views on its essence and essentials, including on the relation between the individual self (jivatman) and God (Krishna)[16] or the supreme self (Atman/Brahman). The Gita famously mentions, in chapter XIII verse 24–25, the four ways to see the self, interpreted as four yogas, namely through meditation (raja yoga), insight/intuition (jnana yoga), work/right action (karma yoga) and devotion/love (bhakti yoga), an influential division that was popularized by Swami Vivekananda in the 1890s.[17][18] The setting of the text in a battlefield has been interpreted by several modern Indian writers as an allegory for the struggles and vagaries of human life.

Etymology

[edit]The Gita in the title of the Bhagavad Gita means "song". Religious leaders and scholars interpret the word Bhagavad in several ways. Accordingly, the title has been interpreted as "the song of God", "the word of God" by theistic schools,[19] "the words of the Lord",[20] "the Divine Song",[21][page needed][22] and "Celestial Song" by others.[23]

In India, its Sanskrit name is often written as Shrimad Bhagavad Gita or Shrimad Bhagavadgita (श्रीमद् भगवद् गीता or भगवद्गीता) where the Shrimad prefix is used to denote a high degree of respect. The Bhagavad Gita is not to be confused with the Bhagavata Puran, which is one of the eighteen major Puranas dealing with the life of the Hindu God Krishna and various avatars of Vishnu.[24]

The work is also known as the Iswara Gita, the Ananta Gita, the Hari Gita, the Vyasa Gita, or the Gita.[25]

Dating and authorship

[

The text is generally dated to the second or first century BCE,[3][4][5][6] though some scholars accept dates as early as the 5th century BCE. [citation needed]

According to Jeaneane Fowler, "the dating of the Gita varies considerably" and depends in part on whether one accepts it to be a part of the early versions of the Mahabharata, or a text that was inserted into the epic at a later date.[26]

The earliest "surviving" components therefore are believed to be no older than the earliest "external" references we have to the Mahabharata epic. The Mahabharata – the world's longest poem – is itself a text that was likely written and compiled over several hundred years, one dated between "400 BCE or little earlier, and 2nd century CE, though some claim a few parts can be put as late as 400 CE", states Fowler. The dating of the Gita is thus dependent on the uncertain dating of the Mahabharata. The actual dates of composition of the Gita remain unresolved.[26]

According to Arthur Basham, the context of the Bhagavad Gita suggests that it was composed in an era when the ethics of war were being questioned and renunciation to monastic life was becoming popular.[27] Such an era emerged after the rise of Buddhism and Jainism in the 5th century BCE, and particularly after the semi-legendary life of Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE. Thus, the first version of the Bhagavad Gita may have been composed in or after the 3rd century BCE.[27]

Winthrop Sargeant linguistically categorizes the Bhagavad Gita as Epic-Puranic Sanskrit, a language that succeeds Vedic Sanskrit and precedes classical Sanskrit.

[28] The text has occasional pre-classical elements of the Vedic Sanskrit language, such as aorists and the prohibitive mā instead of the expected na (not) of classical Sanskrit.[28] This suggests that the text was composed after the Pāṇini era, but before the long compounds of classical Sanskrit became the norm. This would date the text as transmitted by the oral tradition to the later centuries of the 1st-millennium BCE, and the first written version probably to the 2nd or 3rd century CE.[28][29]

Kashi Nath Upadhyaya dates it a bit earlier, but after the rise of Buddhism, by which it was influenced. He states that the Gita was always a part of the Mahabharata, and dating the latter suffices in dating the Gita.[30] based on the estimated dates of Mahabharata as evidenced by exact quotes of it in the Buddhist literature by Asvaghosa (c. 100 CE), Upadhyaya states that the Mahabharata, and therefore the Gita, must have been well known by then for a Buddhist to be quoting it.[30][note

1] This suggests a terminus ante quem (latest date) of the Gita be sometime before the 1st century CE.[30] He cites similar quotes in the dharmasutra texts, the Brahma sutras, and other literature to conclude that the Bhagavad Gita was composed in the fifth or fourth-century BCE.[32][note 2]

Authorship

[edit]In the Indian tradition, the Bhagavad Gita, as well as the epic Mahabharata of which it is a part, is attributed to the sage Vyasa,[34] whose full name was Krishna Dvaipayana, also called Veda-Vyasa.[35] Another Hindu legend states that Vyasa narrated it when the lord Ganesha broke one of his tusks and wrote down the Mahabharata along with the Bhagavad Gita.[9][36][note 3]

Scholars consider Vyasa to be a mythical or symbolic author, in part because Vyasa is also the traditional compiler of the Vedas and the Puranas, texts dated to be from different millennia.[9][39][40]

According to Alexus McLeod, a scholar of Philosophy and Asian Studies, it is "impossible to link the Bhagavad Gita to a single author", and it may be the work of many authors.[9][10] This view is shared by the Indologist Arthur Basham, who states that there were three or more authors or compilers of Bhagavad Gita. This is evidenced by the discontinuous intermixing of philosophical verses with theistic or passionately theistic verses, according to Basham.[11][note 4]

J. A. B. van Buitenen, an Indologist known for his translations and scholarship on Mahabharata, finds that the Gita is so contextually and philosophically well-knit within the Mahabharata that it was not an independent text that "somehow wandered into the epic".[41] The Gita, states van Buitenen, was conceived and developed by the Mahabharata authors to "bring to a climax and solution the dharmic dilemma of a war".[41][note 5]

Pancaratra Agama

[edit]

According to Dennis Hudson, there is an overlap between Vedic and Tantric rituals within the teachings found in the Bhagavad Gita.[47] He places the Pancaratra Agama in the last three or four centuries of 1st-millennium BCE, and proposes that both the tantric and vedic, the Agama and the Gita share the same Vāsudeva-Krishna roots.[48] Some of the ideas in the Bhagavad Gita connect it to the Shatapatha Brahmana of Yajurveda. The Shatapatha Brahmana, for example, mentions the absolute Purusha who dwells in every human being.

According to Hudson, a story in this Vedic text highlights the meaning of the name Vāsudeva as the 'shining one (deva) who dwells (Vasu) in all things and in whom all things dwell', and the meaning of Vishnu to be the 'pervading actor'. In the Bhagavad Gita, similarly, 'Krishna identified himself both with Vāsudeva, Vishnu and their meanings'.[49][note 6] The ideas at the centre of Vedic rituals in Shatapatha Brahmana and the teachings of the Bhagavad Gita revolve around this absolute Person, the primordial genderless absolute, which is the same as the goal of Pancaratra Agama and Tantra.[51]

Manuscripts and layout

[edit]

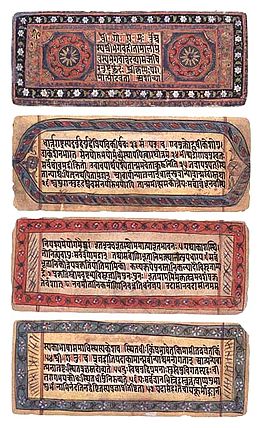

The Bhagavad Gita manuscript is found in the sixth book of the Mahabharata manuscripts – the Bhisma-parvan. Therein, in the third section, the Gita forms chapters 23–40, that is 6.3.23 to 6.3.40.[52] The Bhagavad Gita is often preserved and studied on its own, as an independent text with its chapters renumbered from 1 to 18.[52] The Bhagavad Gita manuscripts exist in numerous Indic scripts.[53] These include writing systems that are currently in use, as well as early scripts such as the now dormant Sharada script.[53][54] Variant manuscripts of the Gita have been found on the Indian subcontinent[55][56] Unlike the enormous variations in the remaining sections of the surviving Mahabharata manuscripts, the Gita manuscripts show only minor variations.[55][56]

According to Gambhirananda, the old manuscripts may have had 745 verses, though he agrees that “700 verses is the generally accepted historic standard."[57] Gambhirananda's view is supported by a few versions of chapter 6.43 of the Mahabharata. According to Gita exegesis scholar Robert Minor, these versions state that the Gita is a text where "Kesava [Krishna] spoke 574 slokas, Arjuna 84, Sanjaya 41, and Dhritarashtra 1".[58] An authentic manuscript of the Gita with 745 verses has not been found.[59] Adi Shankara, in his 8th-century commentary, explicitly states that the Gita has 700 verses, which was likely a deliberate declaration to prevent further insertions and changes to the Gita. Since Shankara's time, "700 verses" has been the standard benchmark for the critical edition of the Bhagavad Gita.[59]

Structure

[edit]The Bhagavad Gita is a poem written in the Sanskrit language.[60] Its 700 verses[56] are structured into several ancient Indian poetic meters, with the principal being the shloka (Anushtubh chanda). It has 18 chapters in total.[61] Each shloka consists of a couplet, thus the entire text consists of 1,400 lines. Each shloka has two-quarter verses with exactly eight syllables. Each of these quarters is further arranged into two metrical feet of four syllables each.[60][note 7] The metered verse does not rhyme.[62] While the shloka is the principal meter in the Gita, it does deploy other elements of Sanskrit prosody (which refers to one of the six Vedangas, or limbs of Vedic statues).[63] At dramatic moments, it uses the tristubh meter found in the Vedas, where each line of the couplet has two-quarter verses with exactly eleven syllables.[62]

Characters

[edit]- Arjuna, one of the five Pandavas

- Krishna, Arjuna's charioteer and guru who was actually an incarnation of Vishnu

- Sanjaya, counselor of the Kuru king Dhritarashtra (secondary narrator)

- Dhritarashtra, Kuru king (Sanjaya's audience) and father of the Kauravas

Narrative

[edit]The Gita is a dialogue between Krishna and Arjuna right before the start of the climactic Kurukshetra War in the Hindu epic Mahabharata.[64][note 8] Two massive armies have gathered to destroy each other. The Pandava prince Arjuna asks his charioteer Krishna to drive to the centre of the battlefield so that he can get a good look at both the armies and all those "so eager for war".[66] He sees that some among his enemies are his relatives, beloved friends, and revered teachers. He does not want to fight to kill them and is thus filled with doubt and despair on the battlefield.[67] He drops his bow, wonders if he should renounce and just leave the battlefield.[66] He turns to his charioteer and guide, Krishna, for advice on the rationale for war, his choices and the right thing to do. The Bhagavad Gita is the compilation of Arjuna's questions and moral dilemma and Krishna's answers and insights that elaborate on a variety of philosophical concepts.[66][68][69]

The compiled dialogue goes far beyond the "rationale for war"; it touches on many human ethical dilemmas, philosophical issues and life's choices.[66][70] According to Flood and Martin, although the Gita is set in the context of a wartime epic, the narrative is structured to apply to all situations; it wrestles with questions about "who we are, how we should live our lives, and how should we act in the world".[71] According to Huston Smith, it delves into questions about the "purpose of life, crisis of self-identity, human Self, human temperaments, and ways for the spiritual quest".[72]

The Gita posits the existence of two selves in an individual,[c] and its presentation of the Krishna-Arjuna dialogue has been interpreted as a metaphor for an eternal dialogue between the two.[d]

Textual significance

[edit]Synthesis prioritizing dharma and bhakti

[edit]

The Bhagavad Gita is a synthesis of Vedic and non-Vedic traditions,[75][b][e] reconciling renunciation with action by arguing that they are inseparable; while following one's dharma, one should not consider oneself to be the agent of action, but attribute all one's actions to God.[14][76] It is a Brahmanical text that uses Shramanic and Yogic terminology to propagate the Brahmanic idea of living according to one's duty or dharma, in contrast to the ascetic ideal of liberation by avoiding all karma.[12] According to Hiltebeitel, the Bhagavad Gita is the sealing achievement of the consolidation of Hinduism, merging Bhakti traditions with Mimamsa, Vedanta, and other knowledge based traditions.[77]

The Gita discusses and synthesizes sramana- and yoga-based renunciation, dharma-based householder life, and devotion-based theism, attempting "to forge a harmony" between these three paths.[78][e] It does this in a framework addressing the question of what constitutes the virtuous path that is necessary for spiritual liberation or release from the cycles of rebirth (moksha),[79][80] incorporating various religious traditions,[81][82][78] including philosophical ideas from the Upanishads[83][6] samkhya yoga philosophy,[6] and bhakti, incorporating bhakti into Vedanta.[77] As such, it neutralizes the tension between the Brahmanical worldorder with its caste-based social institutions that hold society together, and the search for salvation by ascetics who have left society.[84]

Rejection of sramanic non-action

[edit]Knowledge is indeed better than practice;

Meditation is superior to knowledge;

Renunciation of the fruit of action is better than meditation;

Peace immediately follows renunciation.

According to Gavin Flood and Charles Martin, the Gita rejects the shramanic path of non-action, emphasizing instead "the renunciation of the fruits of action".[13] According to Gavin Flood, the teachings in the Gita differ from other Indian religions that encouraged extreme austerity and self-torture of various forms (karsayanta). The Gita disapproves of these, stating that not only is it against tradition but against Krishna himself, because "Krishna dwells within all beings, in torturing the body the ascetic would be torturing him", states Flood. Even a monk should strive for "inner renunciation" rather than external pretensions.[86] It further states that the dharmic householder can achieve the same goals as the renouncing monk through "inner renunciation" or "motiveless action".[79][note 9] One must do the right thing because one has determined that it is right, states Gita, without craving for its fruits, without worrying about the results, loss or gain.[88][89][90] Desires, selfishness, and the craving for fruits can distort one from spiritual living.[89][f]

The Bhagavad Gita is part of the Prasthanatrayi,[94][95] which also includes the Upanishads and the Brahma sutras, the foundational texts of the Vedanta school of Hindu philosophy.[96][g]

Vaishnavism

[edit]The Gita is a revered text in the Vaishnava tradition,[97][98][99][100][101] mostly through the Vaishnava Vedanta commentaries written on it,[101] though the text itself is also celebrated in the Puranas, for example, the Gita Mahatmya of the Varaha Purana.[h] While Upanishads focus more on knowledge and the identity of the self with Brahman, the Bhagavad Gita shifts the emphasis towards devotion and the worship of a personal deity, specifically Krishna.[16] There are alternate versions of the Bhagavad Gita (such as the one found in Kashmir), but the basic message behind these texts is not distorted.[55][102][103]

bhagavadgita