Introduction

During the turbulent years of the early 1960s, students under the Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations (CISCE) board (those preparing for the Indian Certificate of Secondary Education — ICSE — and the Indian School Certificate — ISC) did more than just study. They rolled up their sleeves and knitted sweaters, socks and warm garments for Indian soldiers engaged in the 1962 and 1965 wars. At the same time, India’s first Education Minister, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, envisioned an inclusive, modern education system — and in 1958 CISCE was established in New Delhi to carry forward a rigorous English-medium, holistic curriculum that aligned with that vision. This blog explores those interwoven narratives: students’ social service during wartime, Azad’s educational philosophy, and CISCE’s founding and evolution.

Student-Service in Wartime: ICSE/ISC and the 1962 & 1965 Wars

In the 1962 war (between India and China) and the 1965 war (between India and Pakistan), there were strong calls across India for citizen participation in supporting the armed forces. Many schools affiliated to CISCE responded by organising knitting drives: students, often girls and boys in secondary school, knitted warm sweaters, socks and blankets for soldiers posted in cold forward posts. This effort reflects:

A sense of national duty instilled in students – not only academics but service.

A linkage between schooling (especially in English-medium, affiliated schools) and broader patriotic/social service.

The value of practical activity beyond textbooks, aligning with the broader vision of education as character-building.

While formal official records of every knitted garment may not be compiled, the anecdotal and archival memory of such student-service remains part of the educational culture of that era.

Maulana Azad’s Vision for Education

Maulana Azad believed that education was not simply for the elite or for employment: it was a birth-right of every citizen. He argued that:

“Every individual has a right to an education that will enable him to develop his faculties and live a full human life.”

Key elements of his vision:

Universal access: including rural, marginalised, girls, minorities.

Emphasis on scientific, technical and vocational education alongside liberal arts.

Education as a means of national integration, unity, and social justice (not just credentialing).

The state’s responsibility, not leaving education exclusively to private or elite interests.

Azad’s vision thus set the ideological groundwork for boards and systems that sought quality and access — such as CISCE.

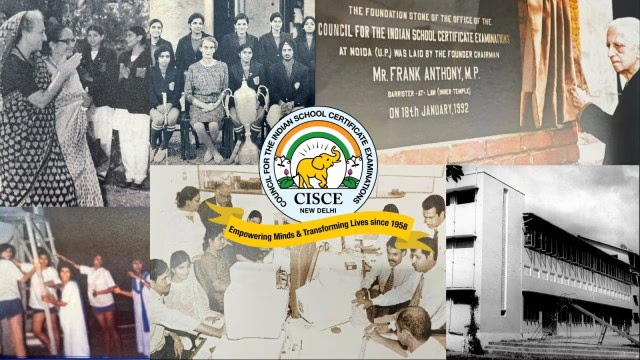

CISCE: Founding and Evolution (1958 onwards)

The Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations (CISCE) was founded in 1958 in New Delhi.

Important points:

The inaugural meeting of CISCE was held on 3 November 1958.

Its motive: to establish a national-level English-medium board offering comprehensive certificates: ICSE (Class X) and later ISC (Class XII).

CISCE aims to serve the nation’s children, empower them for a humane and pluralistic society, and create exciting learning opportunities.

A chronology of milestones:

1963: Examination nomenclature changed from “Overseas Certificate Examination” to Indian School Certificate (ISC).

1967: CISCE registered as a Society under the Societies Registration Act.

1970: First ICSE examination conducted.

Thus, the board launched in the context of India’s post-independence educational reform, aligning with Azad’s vision of modern, equitable, high-quality schooling.

Bridging these Three Threads

Putting the three narratives together gives us a rich picture:

The student-service in wartime reflects how schools under CISCE were socialised into national service and character-formation beyond exam performance.

Maulana Azad’s educational philosophy provides the moral-intellectual framework for why such service and broad education mattered — equality, social justice, nation-building.

CISCE’s formation and growth illustrate a practical institutional vehicle that carried those values into schooling: rigorous curriculum, English-medium access, holistic development.

For students, parents, educators today, understanding this layered history gives deeper meaning to schooling under ICSE/ISC — it’s not just exams, but a legacy of service, vision and institutional evolution.

Why This History Matters Today

It reinforces the value of service-learning in schools: knitting for soldiers is an example of students contributing meaningfully to society.

It underscores the importance of inclusive education: Azad’s vision still resonates with contemporary goals of universal education and equity.

It reminds us of the significance of institutional continuity: CISCE’s evolution shows how educational boards can adapt and maintain standards over decades.

It helps current students appreciate their legacy: knowing that their school board’s roots extend to national service and educational reform can foster greater sense of purpose.

FAQ

Q1: Did all ICSE/ISC students knit sweaters and socks for soldiers during the wars?

A1: While there was no uniform national mandate for all ICSE/ISC students, many schools affiliated to CISCE organised knitting-drives for soldiers in the 1962 and 1965 wars. The practice was more common in certain schools and localities with strong community service ethos.

Q2: What exactly was Maulana Azad’s role in shaping India’s education system?

A2: As India’s first Minister of Education, Maulana Azad spearheaded efforts to democratise education, emphasise universal access (especially for girls and minorities), promote scientific and technical education, and advance the idea of education as a vital element of nation-building.

Q3: Why was CISCE formed when there were other boards like CBSE?

A3: CISCE was established in 1958 to offer an alternative to colonial-era examination systems (such as Cambridge School Certificate) and to provide an English-medium, nationally relevant certificate (ICSE & ISC) that emphasised a broad curriculum and critical thinking.

Q4: How does knitting sweaters for soldiers relate to schooling and learning?

A4: The activity represented an extension of schooling into civic-responsibility and character-formation. It allowed students to engage in real-life meaningful service, developing empathy, discipline, and connection to the nation-building ethos — aligning with Azad’s educational vision.

Q5: How can current schools revive such traditions meaningfully?

A5: Schools can integrate service-learning modules, partner with community or national initiatives (veteran care, disaster relief, social welfare), tie the service to curriculum themes (history, civic education, ethics), and reflect on the legacy of boards like CISCE to motivate students beyond rote learning.

Published on : 11TH November

Published by : SARANYA

Source Credit ; Mridusmita Deka

🛡 Powered by Vizzve Financial

RBI-Registered Loan Partner | 10 Lakh+ Customers | ₹600 Cr+ Disbursed